Focus restoration with restormer

Published:

Intro

I am very happy this week because, after some time working with it, my contribution to the MONAI project has been accepted! For those unfamiliar, MONAI is a PyTorch-based open-source framework for deep learning in healthcare imaging, and I am proud to be part of such a great community because I use their framework a lot.

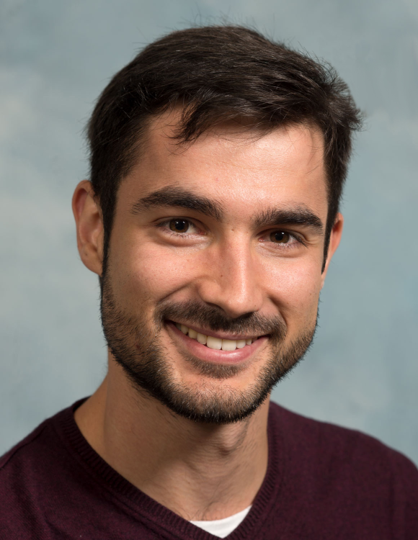

My contribution is a flexible implementation of the Restormer model for image restoration. I first stumbled upon this model because, in my current project, we acquire a lot of images (like… A LOT), and very fast. The project consists of acquiring microscopy images of bacteria under multiple conditions across time using well plates. To capture enough bacteria, we use a 40x objective that moves swiftly between positions, making out-of-focus objects really common. The image below (Figure 1) shows an example of the problem. I used a simple Sobel filter to detect the edges of bacteria, just to illustrate how the bacteria in the center are sharper than on the sides of the image:

Figure 1: Source image (left), Sobel filter edge detection (middle), and focus map (right) showing uneven focus across the field.

Since manually focusing on each object is impossible at this scale, I needed an automated solution that could restore focus computationally.

Tackling the issue

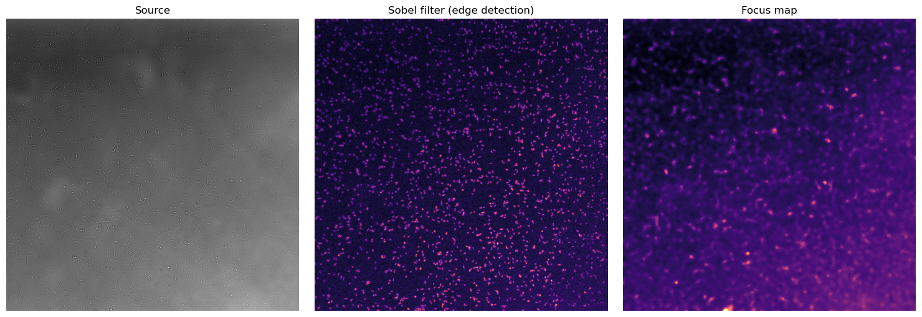

To tackle this, I came up with a simple idea: out-of-focus mainly happens because objects are in different planes. So, I take images at different Z-planes and use the model to infer the perfect focal plane from the out-of-focus images (see Figure 2). Given that our images are quite large and almost always contain some objects in focus and some out of focus, I split the image into quadrants and use as target only the quadrants with the most objects in focus.

Figure 2: Z-stack acquisition (left), off-focus slices as input (middle), and in-focus slices as target (right).

The Restormer model

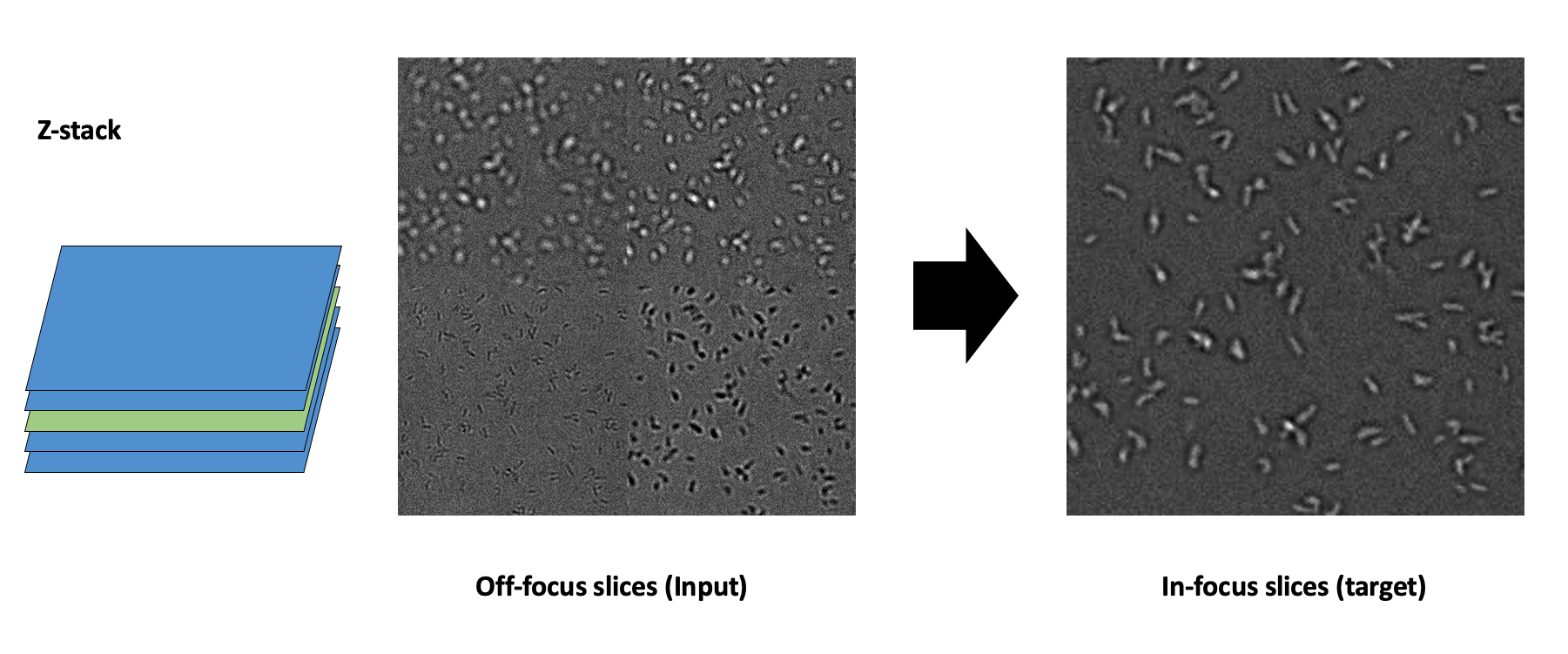

The Restormer, as described by Zamir et al. (2022), is a Vision Transformer specifically designed for high-resolution image restoration. It uses a multi-scale encoder-decoder architecture with skip connections, similar to U-Net, allowing it to capture both global and local image features. The key innovation is that, instead of using spatial attention as in the original Vision Transformer, it uses a combination of spatial and channel attention (what the authors call Multi-Dconv Head Transposed Attention, or MDTA), which allows it to focus on the most relevant features in the image. See Figure 3 for a schematic overview.

Figure 3: Schematic overview of the Restormer architecture, including the UNet-like encoder/decoder architecture, MDTA, and GDFN blocks.

Notice also that one of the key parts is the fact that the original image is also passed to the end of the model. This way, the model can focus on the noise without having to learn the whole image again.

Implementation Details

This implementation extends the original 2D Restormer to support both 2D and 3D operations, making it particularly valuable for volumetric medical imaging. I thought this would be easy because the transformer block does not care about dimensions and the MONAI library already had an UpSample layer using pixel shuffle. However, there was no pixel unshuffle. Thus, I had to implement it myself. For this, I tackle the problem as permutation problem. If you think about it, it is just about moving the dimensions around:

def pixelunshuffle(x: torch.Tensor, spatial_dims: int, scale_factor: int) -> torch.Tensor:

# ...

output_size = [batch_size, new_channels] + [d // factor for d in input_size[2:]]

reshaped_size = [batch_size, channels] + sum([[d // factor, factor] for d in input_size[2:]], [])

# The eureka moment came when I realized the permutation pattern is just collecting all scale factors first,

# followed by all spatial dimensions - it's like separating the "what" (features) from the "where" (locations)!

permute_indices = [0, 1] + [(2 * i + 3) for i in range(spatial_dims)] + [(2 * i + 2) for i in range(spatial_dims)]

# And then, pass everything to the channel dimension while keeping the spatial dimensions intact.

x = x.reshape(reshaped_size).permute(permute_indices)

x = x.reshape(output_size)

return x

After this, everything else was quite simple because the transformer blocks were already dimension-agnostic by design. The next challenge was to give flexibility to the model and to add support for 3D images. The first point is important because the original Restormer was a generic model trained for all kinds of common RGB images. However, in the scientific and medical domain, it is more common to deal with N-channel images. Thus, the researcher should have space to contract or expand the encoder/decoder steps as required for their project. For example, in our case, we only had 2 steps because our image sampling space is quite homogeneous. The second point was relevant because, in the medical field, it is quite common to deal with 3D images (e.g., CT, MRI, etc.).

To give more flexibility to the Restormer, I only had to closely follow the calculation on how the spatial dimensions and channels are calculated at each step:

class Restormer(nn.Module):

def __init__(

self,

spatial_dims = 2,

in_channels = 3,

out_channels = 3,

dim = 48,

num_blocks = (1, 1, 1, 1),

heads = (1, 1, 1, 1),

num_refinement_blocks = 4,

ffn_expansion_factor = 2.66,

bias = False,

layer_norm_use_bias = True,

dual_pixel_task = False,

flash_attention= False,

):

spatial_multiplier = 2 ** (spatial_dims - 1)

# Define encoder levels

for n in range(num_steps):

current_dim = dim * (2) ** (n)

next_dim = current_dim // spatial_multiplier

# ...

# Define decoder levels

for n in reversed(range(num_steps)):

current_dim = dim * (2) ** (n)

next_dim = dim * (2) ** (n + 1)

# In the decoder, it was also necessary to add an extra convolution step to reduce dimensions to make space for the skip connections.

For the encoder, it was very straightforward: the encoder systematically halves spatial dimensions while multiplying by $2^{(spatial_dims - 1)}$ channel dimensions at each step. This is because each spatial dimension contributes multiplicatively to the total channel increase. For the decoder, it was basically the same, but I also added an extra convolution step to reduce dimensions to make space for the skip connections.

Results

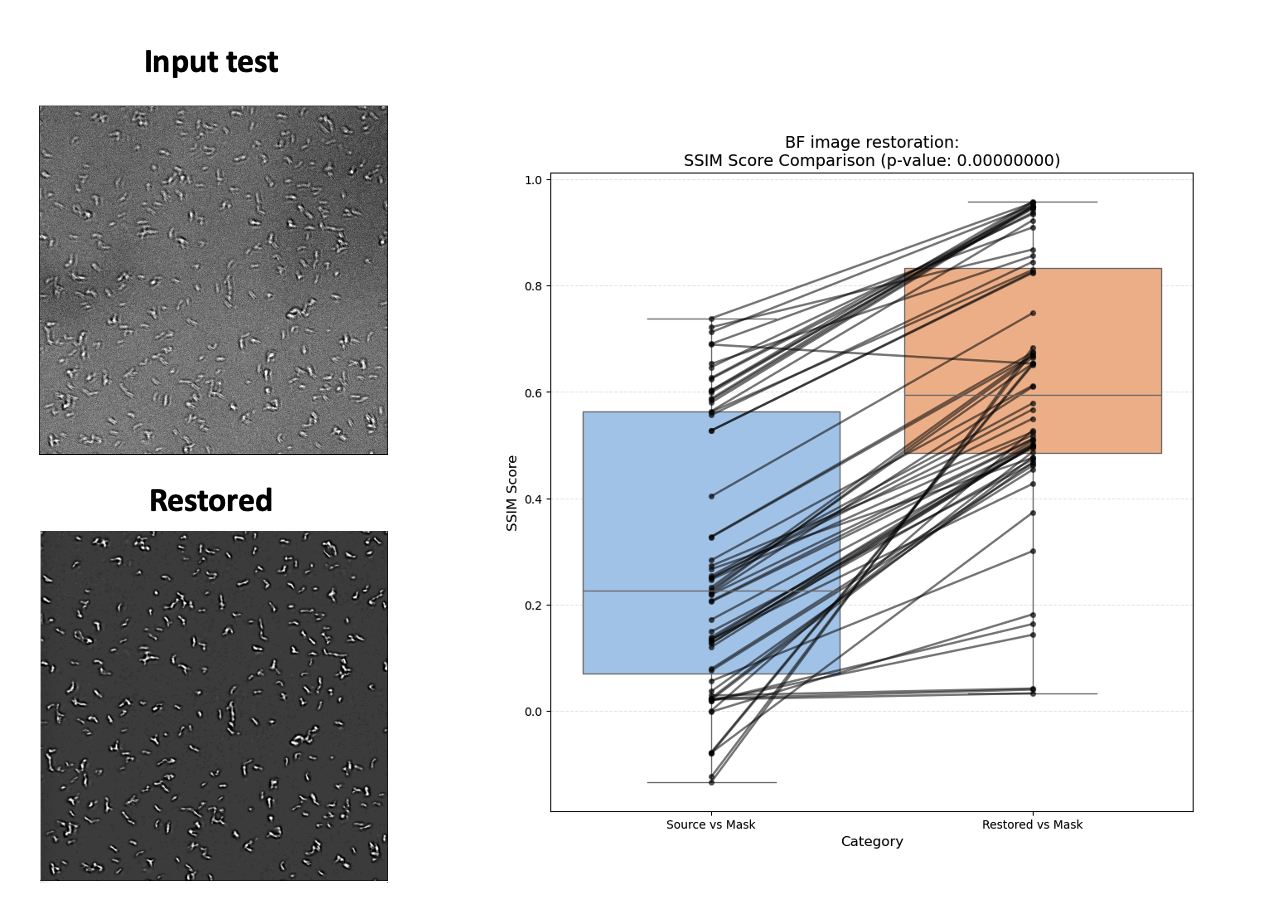

The results were nothing short of amazing. Here’s a before/after comparison (Figure 4):

Figure 4: Left—Input test image (top) and restored image (bottom). Right—Paired SSIM score comparison showing consistent improvement after restoration.

Not only do the restored images look visibly sharper and more defined, but the quantitative results speak for themselves. The SSIM (Structural Similarity Index) scores improved dramatically across the board, as shown in the paired plot. This improvement wasn’t just cosmetic—after restoration, the number of detected objects in our automated pipeline nearly doubled, making downstream analysis much more robust and reliable.

It’s genuinely rewarding to see how a well-designed model can breathe new life into challenging microscopy data. Watching those blurry bacteria snap into focus (both visually and statistically!) was one of those moments that makes all the late-night coding sessions worthwhile.

Things that I learned

Implementing Restormer for MONAI taught me several valuable lessons:

- Channel attention is powerful: The transposed attention mechanism that operates across feature channels rather than spatial dimensions is remarkably effective while being computationally efficient.

- Pixel unshuffle is elegant: Using pixel unshuffle/shuffle as downsampling/upsampling mechanisms preserves information by rearranging it between spatial and channel dimensions rather than discarding it.

- Loss function choice is crucial: Since my goal was to restore images for subsequent segmentation, I used Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) as my loss function. This perceptual metric emphasizes preserving edges and contours rather than just pixel values, which was perfect for my use case. Importantly, I trained a separated model for restoring fluorescent singal, where PSNR was the best loss function because in this case we were only interested in the signal.

- Transformers are data-hungry but efficient: While they require more training data than CNNs, they converge surprisingly quickly and generalize well to unseen data.

- Code Quality: Given the fact that this was a constribution to a large-scale project, I had to pay extra attention to code quality. This meant writing unit tests, documentation, and following the MONAI coding standards. This was a great opportunity to learn about best practices in software development and how to write clean, maintainable code.

Conclusion and Future Work

Contributing to MONAI with this Restormer implementation has been one of the most satisfying projects I’ve tackled recently. The model now lives in the MONAI codebase where others can use it for various medical image restoration tasks beyond my application.